Are We Pushing Our Kids Too Hard In Youth Sports?

What one NBA player's story can tell us about our own children.

Asia Mape

| 8 min read

Stanford graduate Tyrell Terry retired from professional basketball after just two seasons. He shared the news in an Instagram post that he has since taken down. Sports writer Julie Kliegman detailed the once-promising athlete’s near-crippling anxiety in a recent Sports Illustrated article.

He would have frequent panic attacks when he thought about playing

How Terry felt is not unique. In fall 2021, 24% of male and 36% of female athletes “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function,” according to an annual survey from the NCAA. We have an epidemic of young people suffering from anxiety and depression. The pressure we put on our kids around academics and athletics is crippling them. Data from the American College of Sports Medicine indicates that 35% of elite athletes struggle with eating disorders, burnout, depression, or anxiety. A report published by the American Psychological Association said that adolescents between 15-21 are the MOST stressed-out people in this country. New York Times best-selling author and Wharton School psychologist Adam Grant says parents are greatly to blame. We are pressuring our kids to overachieve in all areas of their lives.

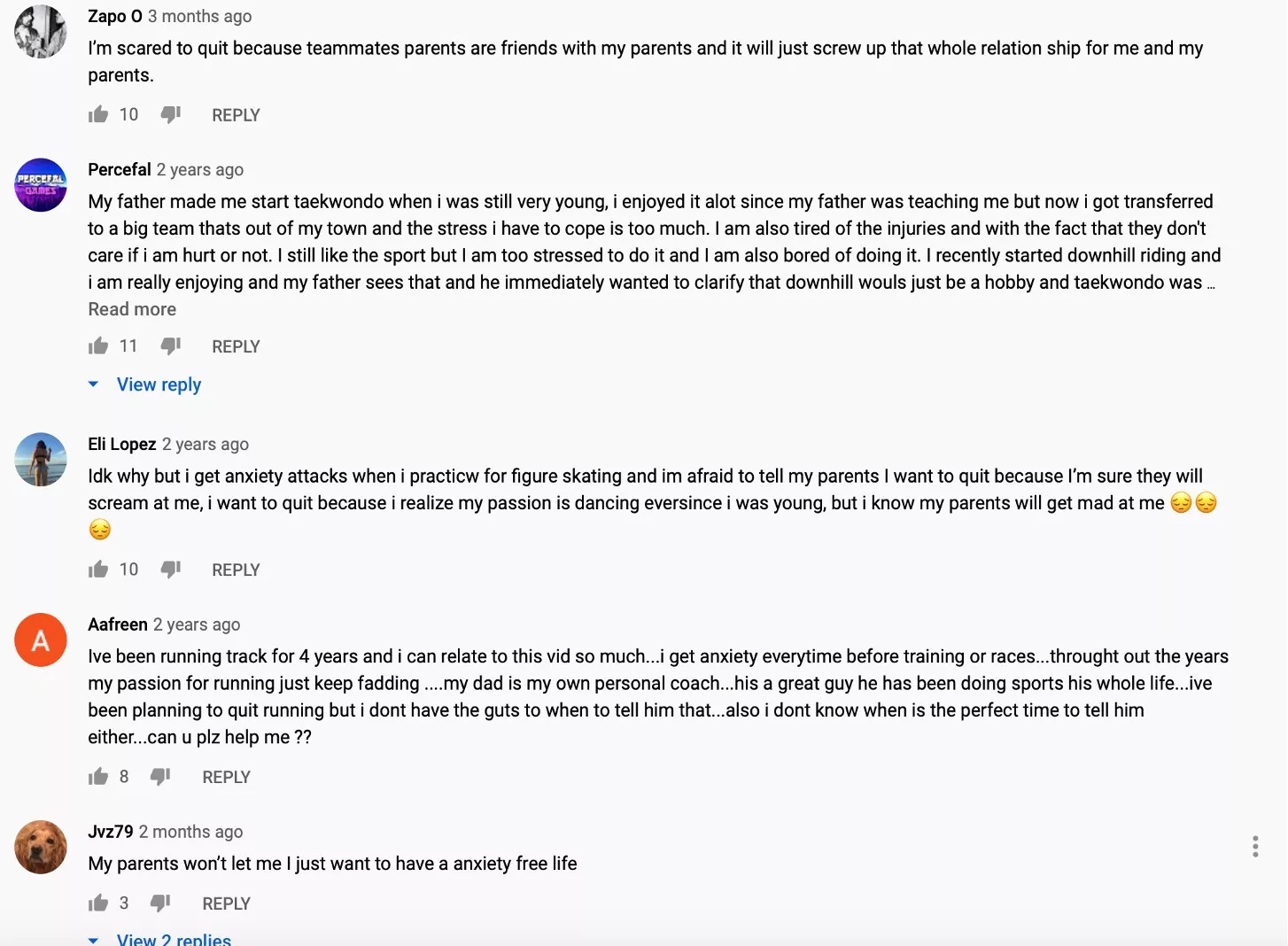

14,000 comments from kids about their parents pressuring them to play sports

But what convinced me that parents own a lot of the blame and rocked me to my parenting core is a TikTok I stumbled on by @Jacob.Roelen captioned, “the worst car ride ever,” talking about his Dad yelling at him on the car rides home from sports. Thousands and thousands of kids responded to that TikTok with heartbreaking pleas.

The common thread across almost all 14,000 comments is that kids feel tremendous pressure from their parents to play sports. If you take the parent equation out of sports, sports are stressful in their own right. We should be their cheerleaders and support system; we shouldn’t be the ones causing their stress. We need to be the ones they come to when they are feeling stressed or anxious.

There is more to me than basketball

Terry, the former Stanford Grad and NBA draft pick who quit, tried to continue to play. He put so much work into basketball and considered it a great honor to play professionally. So he attacked his anxiety with everything he had: therapy, homeopathic methods, and meds, but eventually concluded he could no longer go on. He had an identity crisis, “I wasn’t really doing it for myself.” In the article, his parents aren’t directly blamed, but he says he was “forced to give up the other sports he loved. In his Instagram, he stated, “There is more for me in this vast world, and I’m extremely excited to be able to explore that.”

No longer are we OK with our kids’ activities unless they are a means to an end

I had to come to terms with my own parenting and putting too much pressure on my oldest daughter, and I wrote about the terrible effect it had on her and on our relationship. At some point, I lost sight of what was most important: letting her guide her own journey. I stopped pushing my agenda and gave her the space to discover her own joy and passion.

Kids can no longer do an activity unless it’s a means to an end, a college scholarship, entrance to a top school, or, at the very least, Facebook bragging rights. We have abandoned the idea that playing a sport, learning an instrument, or having a flair for art can have intrinsic benefits, like pure enjoyment or a needed distraction from the everyday stresses of life. So we pour money and time and put a lot of pressure on our kids to master all that they do, and only if they are superior and masters do we consider it to have worth.

You might be familiar with author Kurt Vonnegut’s famous story about meeting an archeologist at a dig who asked him a few simple questions that would change his life. Here’s how Vonnegut retells that chance encounter:

“Do you play sports? What’s your favorite subject? And I (Vonnegut) told him, no, I don’t play any sports. I do theater; I’m in choir, I play the violin and piano, and I used to take art classes. And he went WOW. That’s amazing! And I said, Oh no, but I’m not any good at ANY of them.” And he said something then that I will never forget and which absolutely blew my mind because no one had ever said anything like it to me before. “I don’t think being good at things is the point of doing them. I think you’ve got all these wonderful experiences with different skills, and that all teach you things and make you an interesting person, no matter how well you do them.”

Kristen Jones, author of “Raising Empowered Athletes” and #RaisingAthletes podcast host, describes it in a piece she wrote for Ilovetowatchyouplay about the pressure to be perfect. “Gone is the day when the parenting motto was “Try everything.” As a society, we’ve become obsessed with being superior and the outcome of winning, which translates to specializing early and pressing kids to over-train and become mini-adults approaching sports like a job.” And this “job” we’ve created dramatically adds to the mental health crisis for our young people in this country.

There is hope

So what can we do? The good news is that, as youth sports parents, we have a lot of control over changing this. Starting from a very young age, how do you frame their sports, college choices, and academic standards? Are we only discussing Stanford and The University of Michigan in the home? Or are we talking about the many great choices out there for college and making sure they know that there is a college for everyone or even a trade school? Do we discuss the great benefit of playing D2, D3, or even club sports in college?

There are so many paths to success or, even more importantly, to joy and fulfillment. If college is the goal, it’s become nearly impossible to get into the top colleges in our country, so by making them the gold standard, we are putting unrealistic expectations on our kids and causing them so much stress in trying to reach those goals. All the AP and honors classes, the test prep, the tutors, doing homework long into the night, add crazy sports schedules on top of that. Something has to give, and it’s their mental health.

Frame college, their academics, and their sports in more achievable, reachable ways. Stress the journey and that sports are preparing them for life and the joy of playing with friends and classmates. Give them space and acceptance to quit or take time away if they need it. Stop talking about improving, comparing them to other kids, telling them they need sports to get into college, and pushing them to make the all-star team, the first team, or Varsity.

We all have the power to change what is happening right now. We must look inward and decide if we are OK with stressed out, anxious kids, and in extreme cases, depressed or even suicidal…or are we going to buck the system and let them know that it’s OK not to be perfect? And that we all made a ton of mistakes along the way and that they can still have a wonderful life even if they don’t get into Vanderbilt or make varsity.

Jones shares practical tips in this article, but she sums it up with this, “Kids will still get messages from their peers and the media, but if you are their rock at home, reinforcing the message that it’s OK NOT to be perfect and that it’s OK to slow down and enjoy the process, then we can help them to be more balanced and happy. Stop force-feeding them the wrong and dangerous message that they better get on the high-speed train going nowhere or all of life’s riches will pass them by; instead, preach balance, fulfillment, and finding joy. If they are self-motivated and driven to succeed in sports and school at a high level, that’s great. But let them drive that bus and instead be passengers in the back of that bus, cheering them on.

Asia Mape runs ilovetowatchyouplay.com, a site for parents who want to raise happy, healthy and successful athletes. A version of this story appeared on that site first.